In 1969 Charles Eames sketched out a rough visualization of the design

process for an exhibition at the Louvre entitled “What is design?” It

consisted of three loose amoeba-like graphical elements floating in the

void of his sketchbook, overlapping, intersecting, and connecting to create

the most idyllic representation of what design should be. The three

layered forms respectively constitute the interests and concerns of the

designer, the genuine interest of the client, and concerns of society as a

whole. Where the subsets intersect lay the common ground where

designers can work with “conviction and enthusiasm”. Like much of the

Eames’ work, the beauty is found in the objects’ duality. Floating

gorgeously in clarity and in the absence of pretense… churning below are

the complexities brought not only by the designer and the client, but

society as well. We designers are given the daunting task of mapping the

blurred sovereignty where morals, economics, and personal goals

intersect.

We are at the beginning of a new epoch of human viability, where all

economies and ecologies are becoming globalized, related and integrated.

More than any other discipline, design has placed us, for better of for

worse, in this position.

For the last 100 years graphic design has been an instigator, purveyor,

and documentarian of cultural change. Increasingly, however, graphic

design is becoming segmented and predictable. Rarely found is a designer

who creates work that satisfies the needs of the designer, the client and

humankind. This, paired with the narrow selection of tools (primarily

software) which we allow ourselves to use contributes to the disposable

conduit that makes up the majority of design encountered daily. Craft and

vocation are left behind, leaving the mass media with unchallenging, corn-

fed design for the people.

By falsifying our skills as creative artists and knowingly swimming out

to the undertow of “autistic economics”[1], where unemployment,

inequality, and globalization prevail, finding the area where the “designer

can work with determination and enthusiasm” becomes all the more

difficult. We designers will not find this idyllic area alone. Working with

colleagues both in and outside of the realm of visual communications

cultivates understanding. For as the globe is rendered increasingly

accessible by communication technologies and forces of economic

consolidation, it is at the same time segmented by diverse national, racial,

and ethnic identities. The contradictory mandate of designers in the 21st

century is to create visual scripts which can communicate across cultural

and linguistic barriers without flattening diversity into caricature.[2]

The collective conscious of the design community is beginning to

reevaluate its societal role. In his essay published by the American

Institute of Graphic Arts, The Citizen Designer, Rick Poyner states, “We

must ensure that design, as an interdisciplinary way of thinking, becomes

an integral and equal component of significant public initiatives.”[3]

Melding such initiatives with our client’s ideals and our morals, we can

benefit all parties involved. Through these means Eames’ pluperfect land

seems all the more attainable.

1. Campbell, Deborah, “Kick it Over! –The Rise of Post-Autistic Economics” in Adbusters #55, (Sep-Oct 2004)

[2] Lupton, Ellen and Miller, J. Abbott, “Critical Wayfinding,” in ed., Susan Yelavich, The Edge of the Millennium, (New York: Whitney Library of Design 1993): 220-232.3.

[3]. Poyner, Rick, “The Citizen Designer” in Trace: AIGA Journal of Design V1/N4 (2003) |

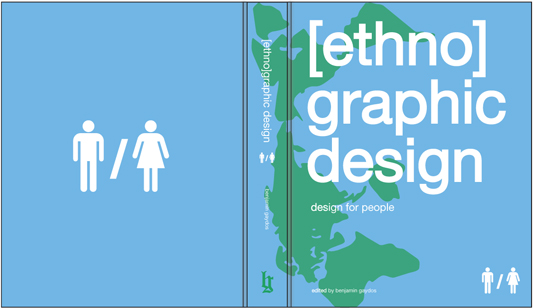

a statement of intent, 2006

Here's one of a few essays that I've written over the last few years. To view [ethno]graphic design, my thesis (which has a fair amount of words) click here. |